There are no items in your cart

Add More

Add More

| Item Details | Price | ||

|---|---|---|---|

NCERT Science Notes - Class 10

Chapter 5 - Life Processes

Welcome to AJs Chalo Seekhen. This webpage is dedicated to Class 10 | Science | Chapter 5 - Life Processes. The chapter delves into the intricacies of life as we unravel the essential processes that define living organisms. From respiration to growth, reproduction to response, and metabolism to organization, our comprehensive notes provide a deep understanding of the mechanisms that sustain life. Explore this enlightening chapter and unlock the secrets of vitality.

Class 10 NCERT metals and non metals notes ajs, cbse notes class 10 ajslearning, cbse notes ajs, ajs notes class 10, ajslearning, ajs chalo seekhen

NCERT Science Notes - Class 10

Chapter 5 - Life Processes

To differentiate between living and non-living entities, we often look for certain characteristics or evidence of life. Here are some common criteria used to determine if something is alive:

Regarding your mention of molecular movements, yes, molecular movement is essential for life, especially at the cellular level. Cells constantly undergo molecular movements to transport nutrients, eliminate waste, and carry out various biochemical processes necessary for survival.

Viruses, as you noted, are a unique case because they lack metabolic processes and cannot independently reproduce. Their status as living or non-living entities is a subject of debate among scientists.

In summary, the characteristics of life involve a combination of visible and microscopic features, and the presence of one or more of these criteria can help determine whether an entity is alive or not.

Life processes are essential functions that maintain life in living organisms, whether they are actively doing something or at rest. These processes include:

In single-celled organisms, these processes are simpler because the entire surface of the organism is in contact with the environment, allowing direct exchange of materials. However, in multicellular organisms, the complexity increases due to the need for specialized tissues and systems to perform these life processes efficiently. These processes are vital for maintaining the structure and function of living organisms, and they require energy to occur.

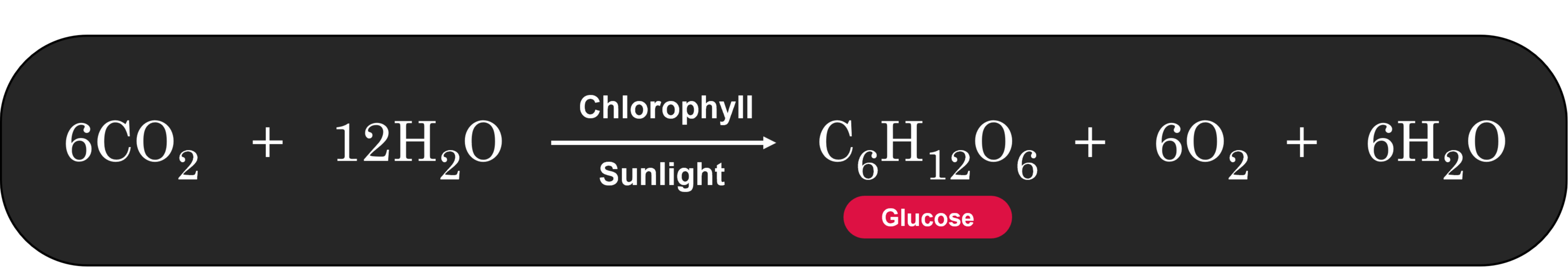

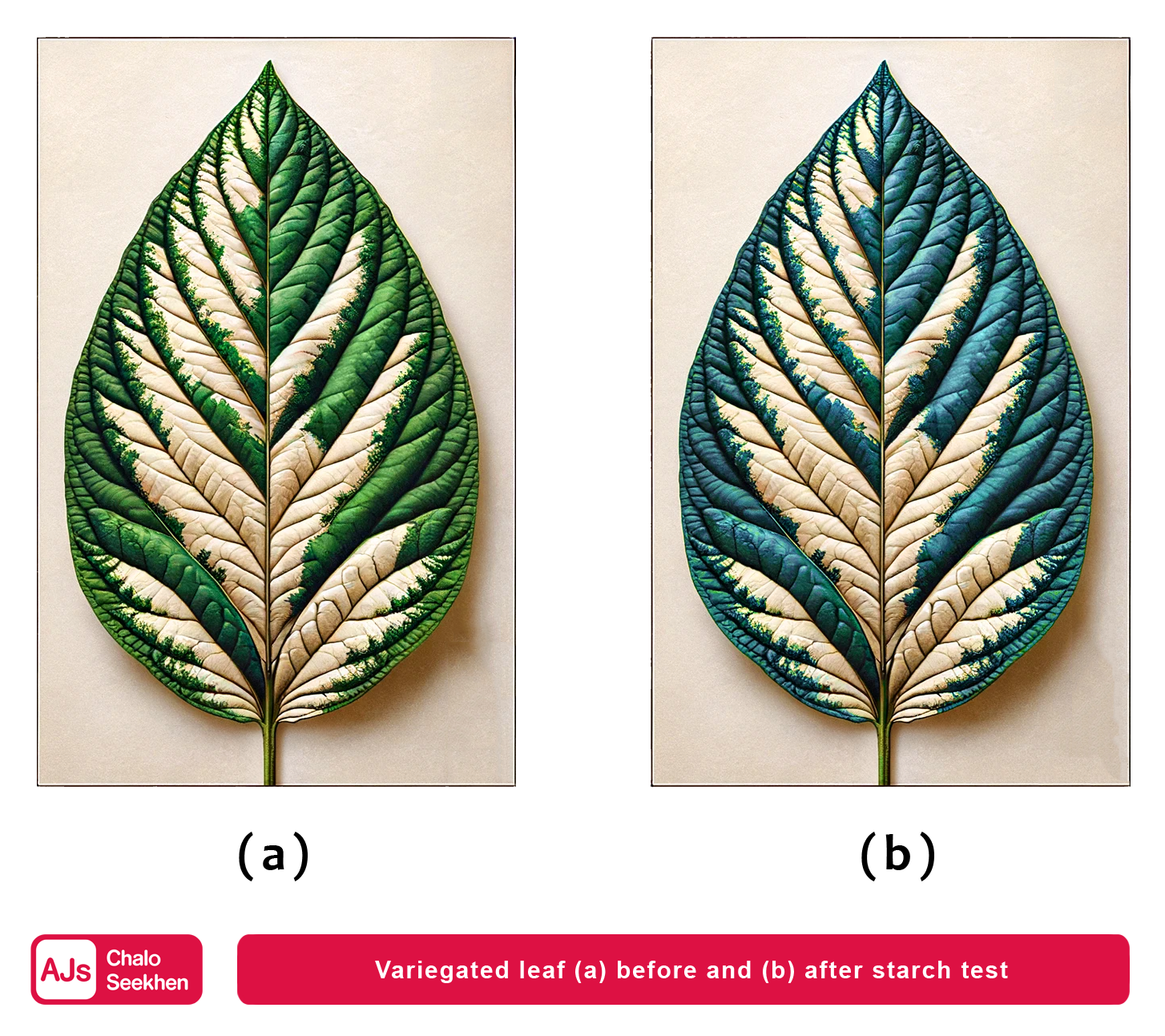

This detailed explanation of autotrophic nutrition, specifically through the process of photosynthesis, highlights the importance of autotrophs in the ecosystem. They not only provide their own energy but also serve as the primary producers in the food chain, supporting heterotrophs (like animals and fungi) that cannot produce their own food.

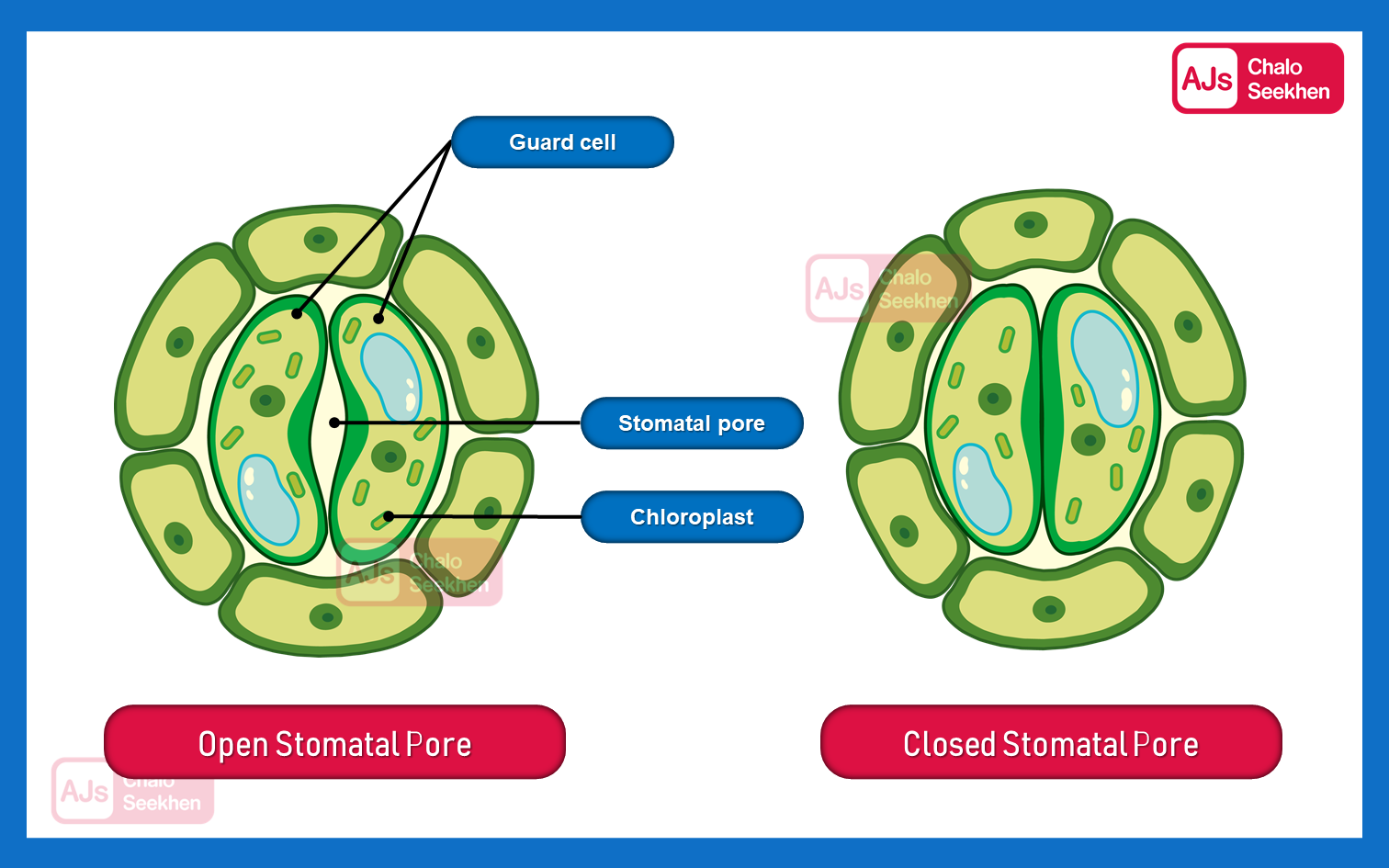

This system allows the plant to balance its need for carbon dioxide for photosynthesis with the need to minimize water loss, especially in conditions where water is scarce or during times when photosynthesis is not occurring, such as at night.

Definition: Heterotrophic nutrition is the mode of nutrition in which organisms rely on other living organisms for their food, as they cannot produce their own.

Adaptation to Environment: Each organism is adapted to its environment, and the type of nutrition depends on:

Overview: The process of obtaining and digesting food varies across organisms, largely depending on their complexity and structure. In simple, single-celled organisms, food intake and digestion occur differently compared to multicellular organisms.

Nutrition in Single-Celled Organisms:

The Alimentary Canal: The human digestive system, or alimentary canal, is a long tube extending from the mouth to the anus, with different sections specialized for various functions involved in digestion and nutrient absorption.

Process of Digestion: When food enters the body, it moves through the different parts of the alimentary canal, each performing a specific role in breaking down the food so that nutrients can be absorbed.

In humans, various types of food pass through the same digestive tract and are processed to ensure they become small, uniform particles. This is achieved by:

Dental caries, or tooth decay, is the gradual softening of the enamel and dentine layers of the tooth. The process begins when bacteria act on sugars, producing acids that lead to enamel demineralization.

Respiration is the process where cells utilize nutrients to release energy essential for life processes. Different organisms carry out respiration in various ways, often depending on the availability of oxygen.

Activity 5.4: Observing Carbon Dioxide in Exhaled Air

Activity 5.5: Observing Fermentation by Yeast

ATP (Adenosine Triphosphate):

Human Respiratory System

Harmful Effects of Tobacco:

5.4.1 - Transportation in Human Beings

Activity 5.7

Transportation System in Humans

Role of Blood in Transport:

The heart is a muscular organ, roughly the size of a fist, that pumps blood throughout the body. It ensures the circulation of oxygen-rich blood and carbon dioxide-rich blood without mixing the two, maintaining efficient oxygen delivery and carbon dioxide removal.

Structure and Chambers of the Heart:

The heart's separation into the right and left sides plays a crucial role in preventing the mixing of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood, which enhances the efficiency of oxygen supply to the body. This separation is particularly advantageous for animals with high energy demands, such as birds and mammals, which require a constant energy supply to maintain their body temperature.

Heart Structures in Different Animals

Double Circulation

In vertebrates with four-chambered hearts (like mammals and birds), blood circulation is referred to as double circulation because:

Definition: Blood pressure is the force exerted by circulating blood against the walls of blood vessels.

Types of Blood Pressure

Definition: Blood vessels are the network of tubes that transport blood throughout the body, playing a crucial role in the circulatory system.

Types of Blood Vessels

Blood Flow Process

Definition: Platelets, or thrombocytes, are small, disc-shaped cell fragments in the blood that play a crucial role in hemostasis (the process of stopping bleeding).

Function of Platelets

Definition: Lymph, also known as tissue fluid, is a clear, colorless fluid that is similar to blood plasma but contains fewer proteins and is found in the intercellular spaces of tissues.

Formation of Lymph

Functions of Lymph

Plants require various raw materials for growth and energy, primarily absorbed through their roots from the soil. The transportation of these materials, along with energy, occurs through specialized tissues in the plant. Here’s an overview of the transportation systems in plants:

Absorption of Raw Materials

Transportation Tissues

Plants have two main types of vascular tissues responsible for transportation:

The transport of water in plants primarily occurs through xylem tissue, which consists of interconnected vessels and tracheids. This system facilitates the movement of water from the roots to the leaves and other parts of the plant. Here’s how the process works:

Mechanism of Water Transport

Activity 5.8: Observing Water Transport

Objective: Compare the effects of transpiration in a potted plant and a stick.

While we have discussed the transport of water and minerals through xylem, it's equally important to understand how plants transport the products of photosynthesis and other metabolic substances. This process is known as translocation, which occurs in the phloem.

Key Aspects of Translocation

Excretion is the biological process through which organisms remove harmful metabolic wastes from their bodies. While gaseous wastes from photosynthesis or respiration can be eliminated easily, nitrogenous wastes generated from metabolic activities need to be specifically removed.

5.5.1 - Excretion in Human Beings

The excretory system in humans consists of:

Think it Over!

Organ Donation is a noble act of giving an organ to someone in need, often due to organ failure caused by disease or injury. Key points include:

Plants utilize distinct strategies for excretion compared to animals. Key points regarding plant excretion include:

CBSE Class 10 | Science | Chapter 5 - Life Processes

CBSE Class 10 | Science | Chapter 5 - Life Processes

Dedicated team provides prompt assistance and individual guidance.

Engaging visuals enhance understanding of complex concepts.

Engaging visuals enhance understanding of complex concepts.

Assess understanding and track progress through topic-specific tests